The Zero to 60 Program: How to start running or return after an injury

We love helping injured runners get back to running. It's always one of our top priorities when we start working with a runner who's dealing with an injury that is preventing them from running. However, returning to running after time off without aggravating an injury (or developing a new one) can be tricky. The same is true of new runners who are just getting started.

The magic of starting or returning to running without suffering pain or an injury is a slow, gradual buildup of running volume. Too often, runners, especially experienced runners who have taken time off for injuries, don’t allow enough time to build up volume. They build volume too aggressively, or have large week-to-week spikes in their volume. This can result in persistent nagging injuries, or new injuries.

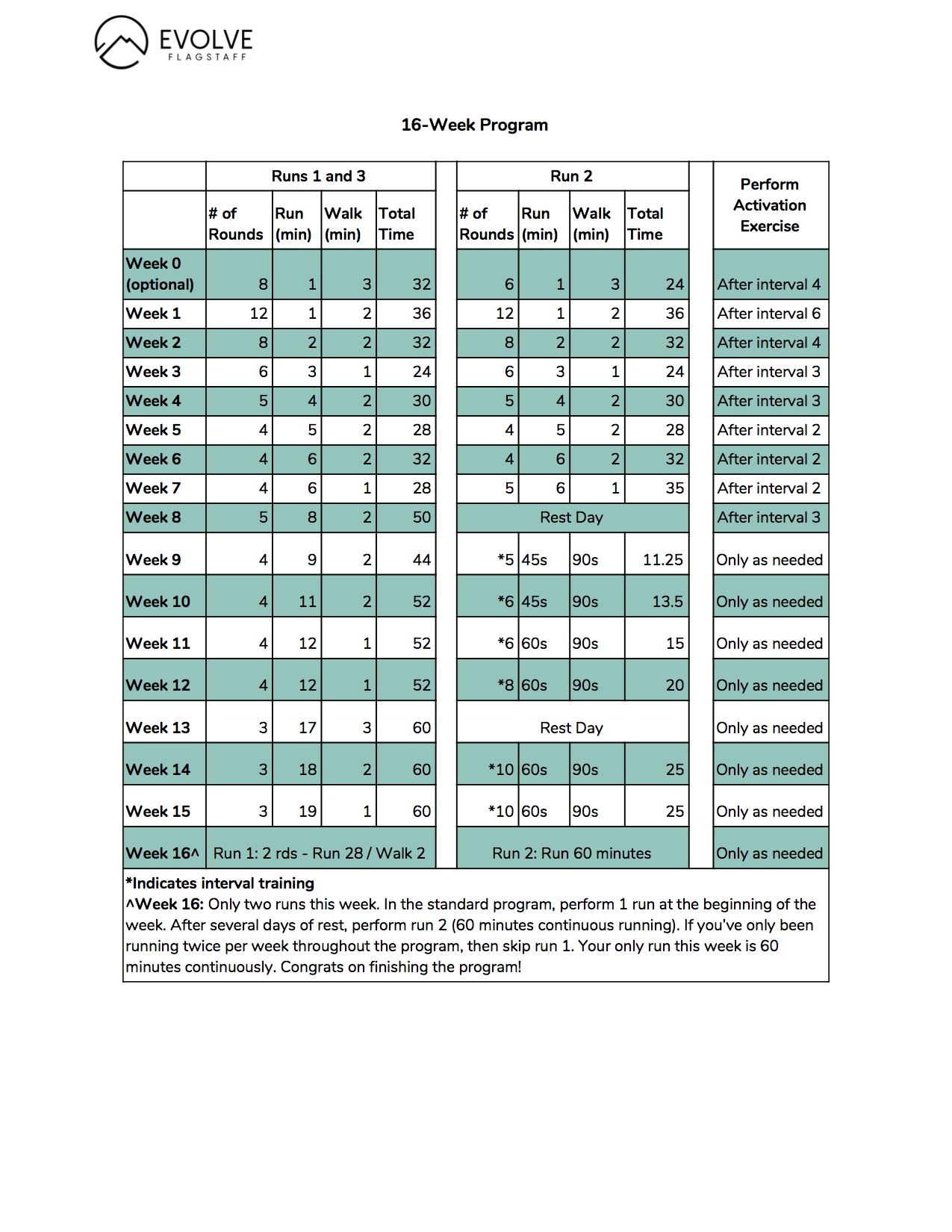

While we can never prevent all injuries, it is possible to reduce injury risk with the right program design. We've created a 16-week program and an 8-week program that follow the most up-to date research recommendations on volume progression and training load. The goal of both programs is to gradually build volume, progressing to running 60 minutes continuously. We're excited about these programs. We went deep into the weeds: we read a dozen research articles and even more blog posts about what works, set up a bunch of spreadsheets, and ran calculations of acute:chronic workload ratios. The programs look simple, but there's a lot that went into their design.

The accelerated program ramps up volume faster, and so we recommend it only to more experienced runners who have consistently held a weekly running volume of several hours, or more than 20 miles. For new runners or those who have been away from running for a long time, the 16-week program will progress more gradually.

Click the image of each program to download a PDF, and read below for instructions.

General Instructions:

- Three workouts are programmed each week. Try to complete each run with at least one day in between.

- For the majority of the workouts, you will alternate between walking and running. We recommend walking at a moderate or fast pace, but running at an easy or moderate pace. On a scale of 1 to 10, try to keep your exertion at about a 5. Resist the urge to make each running interval fast-paced or a sprint. This is especially important in the first few weeks of the program when the run segments are relatively short. Unless you are performing intervals (these are specified), run at an easy or moderate pace. Speed will come after we build volume and consistency.

- We start adding speed work halfway through each program. Especially in the beginning, do not make these an all-out sprint, but rather a quick pace that would be difficult to hold for more than 3-4 minutes. Focus on a fast cadence and landing lightly on your feet. On a scale of 1 to 10, try to keep your exertion at about an 8. Progress towards a full-sprint as you get accustomed to speed work.

- Week 0 is optional, but recommended if you are brand-new to running, or if you haven’t run in more than 6 months.

How should I warm up?

Glad you asked! A proper warm up is essential. The goals of any warm up are to 1) Increase the body and tissue temperature; 2) Prepare the joints for the upcoming range of motion demands; 3) Activate essential stabilizing muscles; and 4) Practice proper technique and prepare the nervous system for upcoming motor control demands.

Complete the following warm up routine prior to every run:

Click above to view a YouTube playlist of each warm up exercise.

- 1-2 minutes: Jump rope or lightly jog in place. Focus on landing softly and quickly.

- 10 Quad / Ham Hinges each side

- Clam shells to fatigue, or 40 reps, each side

- 10 side squats each side

- Posterior tibialis activation to fatigue, or 40 reps, each side

- 10 air squats

- Banded side steps, to fatigue, or 1-2 minutes

- 10 single leg bounds each side, gradually increasing the distance

- If you are performing an interval workout, follow this with 1-2 minutes of running at a gradually increasing speed.

This warm up is an essential part of the program and vital to reducing injury risk. Watch the YouTube videos, and start incorporating them right away. After some practice, this should take 10 minutes or less.

What are the “activation exercises”?

These are simple exercises (often taken from your warm up) that are performed during the middle of your running workout is an excellent way to prevent muscle inhibition and gait changes with fatigue. It helps to avoid pain-related plateaus in running volume.

Complete the activation given to you in physical therapy as indicated in the program. This means to stop your running workout for 1-2 minutes to complete the exercise, then resume running. The activation exercise can take the place of a walking interval.

If you start to feel some type of pain coming on during a run, or an injury returning, then stop immediately and perform an activation exercise. This often helps the pain to subside.

If you are self-treating an injury, try one of the following activation exercises for a history of the following injuries:

Hip pain / knee pain / “IT band syndrome”: Clam shells or side steps

Ankle pain / foot pain / “shin splints”: Posterior tibialis activation

What if I miss a workout?

If you just miss one workout and you are otherwise feeling good and strong, then you can progress to the next week. However, try not to do this too often. Alternating between two and three workouts per week introduces spikes in your training volume that could increase your injury risk. If you’re finding it two hard to get three runs in consistently, then perform the entire program with just two runs per week (see below).

If you miss more than one workout in a week, then just repeat that week again. We need to build consistent volume, and it’s best not to rush this process.

If you miss a few weeks in a row, then we recommend that you backtrack. A good rule of thumb is to go back as many weeks in the program as you missed. (So, for example, if after week 8 of the program you don’t run for 3 weeks, then pick back up at week 5).

What if I can only run twice per week?

If you can only run twice per week, then just perform Runs 1 and 2 with a few days of rest in between each. The program was designed to still meet our acute:chronic workload parameters even with just two runs per week.

However, we do not recommend alternating between two and three runs per week. This adds too many spikes to your training volume. Try to plan ahead and be consistent with either 2 or 3 runs per week.

Additionally, we don't recommend running just once per week. Research on running injuries suggests that running just once per week or more than 5 times per week is associated with greater injury risk.

What if a week is too difficult?

If any given week is too difficult for you, repeat the prior week prior for 1-3 additional weeks, and then attempt to progress again.

What if I feel an injury coming on?

Some soreness is normal as you progress your running. However, you’ll want to pay attention to any nagging aches and pains that feel more severe, more consistent, or of a different quality than normal soreness.

If you feel any potential injuries start to creep up, consider going back a few weeks in the program, or repeating your current week several times. You may have simply progressed too fast. Even with the best program possible, there is still natural variation.

If this doesn’t resolve your injuries, consider scheduling a physical therapy evaluation so we can address it right away. If something hurts, don’t wait more than 2-3 weeks before you get it checked out. It’s much easier to resolve problems if we address them in their acute stage.

How are these programs designed?

Many runners have heard the conventional wisdom of the “10% Rule”: To reduce injury risk, don’t increase running volume more than 10% per week. However, this actually hasn’t been supported by peer-reviewed literature (link). There actually seems to be more flexibility in the way that we progress volume. One paper suggests that only larger increases of above 30% should be of concern (link).

These programs were developed using a more nuanced concept called the “acute:chronic workload ratio.” It's showing more promise in reducing injury risk than a simple linear percentage (link). To apply it, we look at both current weekly volume, as well as the last several weeks of training. This makes sense, because each week of training is not performed in a vacuum. Your fitness progresses week-to-week. To calculate the acute:chronic workload ratio, we divide the current week’s planned volume by the average volume of the past four weeks. The “sweet spot” for injury risk reduction seems to be between 0.8 and 1.3. (If you’re a nerd like us, then we have some great spreadsheets for you.)

So, we designed this program to keep the acute:chronic workload ratio between 0.8 and 1.3 for both programs, and for runners completing two or three runs per week. We varied walking times when volume increased as well. We also kept an eye on intensity, and carefully added speed work along. The 16-week program also includes several rest days to help manage overall training load. Finally, clinical experience has shown us that incorporating activation exercises during workouts can help to stave off fatigue-related neuromuscular inhibition, so we included this as well.

Why a run / walk program?

We designed both of these programs as run/walk programs for a few reasons. First, it makes them more accessible to new runners, or runners who have taken a lot of time off. Second, adding in walking intervals allows us to progress running volume greater than continuous running alone. We couldn't find any research to support this, but we also believe that a run/walk program will help reduce fatigue-related neuromuscular inhibition of key muscles such as the gluteus medius or posterior tibialis. Some running coaches also say that run/walk programs can actually lead to faster average running times, and more people are able to complete them.

What should I do after the program ends?

First, congrats on finishing the program! You’ve built up capacity to run at least two hours per week. From here, you can transition into a standard running training program for a specific goal distance, such as a 10k, half-marathon, or marathon. Or, you can opt to run on your own, freed from any specific training schedule. This can be quite liberating. If you’re interested in completing a race, it can be extremely helpful to work with a running coach.

We also designed three additional programs that continue the progression from here. They pick up right where these left off. Check them out here.

Struggling with a running-related injury? Click the button below to schedule to talk about your issues and questions with a Doctor of Physical Therapy. We'll develop a strategy together to help you reach and exceed your goals.