Superficial peroneal nerve injury in a professional runner: A case study on the importance of diagnosis

There’s a debate in the physical profession right now about whether or not a structural diagnosis of an injury matters. Here at EVOLVE, we think that in most cases, the structure matters, and matters a lot. Patients who have gone to physical therapy elsewhere are often surprised by our focus on diagnosis in the initial evaluation.

There’s a few main reasons why diagnosis is central to our process. With a proper diagnosis, we can:

Give a more accurate prognosis based on rates of tissue healing.

Provide targeted strategies to avoid aggravation of the injured structure

Deliver more focused hands-on treatments to decrease symptoms and optimize the healing response

Choose the most effective therapeutic exercises, so our patients have just a few key things to focus on, rather than a long list of scattershot exercises

Get our patients back to doing what they love, quickly (this is perhaps most important!)

In this post, we’re going to share a case study of a professional ultramarathon runner in which diagnosis was critical to a fast return to running. We’ll first share the subjective report, and examination findings. We’ll then discuss two popular treatment approaches, and why they likely would not have worked for this patient. Finally, we’ll share our treatment and thought process, along with her results.

Subjective History:

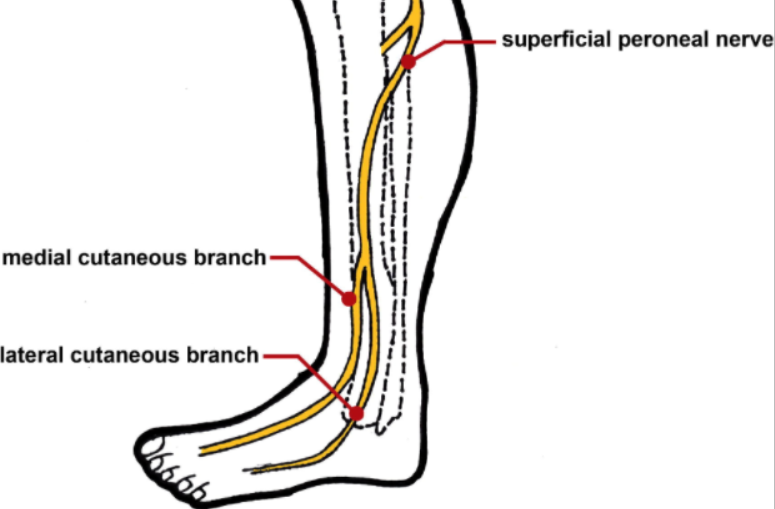

The superficial peroneal nerve branches from the common peroneal nerve just below the fibular head, then runs down the lower leg. Link to image source.

The patient is a 27 year old competitive ultrarunner who presents with a primary complaint of right lower leg/ankle pain that began approximately 2 weeks ago after slipping and falling on ice. She thinks she may have had an inversion ankle sprain. She describes her pain as sharp, with occasional tingling and/or numbness over the anterior ankle, extending to the dorsum of the foot and up the lower leg when it is at its worst. She has significantly reduced running volume due to pain. She has had pain during and after running, initially subsiding quickly, but now lasting for 1-2 days. She has attempted self-management with stretching and self-massage.

She has an important 100km race on Saturday in which she would like to participate, if possible.

Objective Findings:

Normal talocrural dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, subtalar inversion/eversion, hallux extension, and midfoot composite motions bilaterally.

Mild, vague report of pain with a combined motion of plantarflexion and inversion.

Basic medial and lateral ligament stress tests not painful, with no indication of laxity.

Strong and pain-free resisted tests of the anterior tibialis, posterior tibialis, peroneals, extensor digitorum longus, and toe flexors. Tenosynovitis stretch tests of these muscles were not painful.

Tibiofibular syndesmotic squeeze test negative.

No laxity of the proximal tibiofibular joint, or pain with motion testing.

Concordant tingling with sustained (30-45 seconds) straight leg raise test with addition of inversion.

Concordant tingling and pain with deep palpation over approximate location of the superficial peroneal nerve at the level of the extensor retinaculum.

Decreased control of single leg balance on the injured side.

An impairment-based approach targets “impairments” found during the initial evaluation. You can usually think of these as positive exam findings, or things that are difficult for the patient to perform. This patient had pain with plantarflexion and invesion, but no motion limitation, and slightly impaired balance. Aside from that, she didn’t actually have many relevant impairments! So with an impairment-based approach, we would have been stuck. Perhaps we could have found more impairments if we kept digging (everyone has an asymmetry or muscle weakness somewhere), but that probably would not have been the best use our time.

A “graded exposure approach” involves a gradual reintroduction of painful stimulus. Patients are typically instructed to cautiously begin performing the motion that causes symptoms. Using an idea called “edgework,” patients bump into their pain, and then back off, and the hope is to gradually increase tolerance to the painful activity. So, the treatment for this patient may have been to begin performing plantarflexion and inversion. But as luck would have it, the patient had already attempted this herself, and it was only exacerbating symptoms. She had attempted running less, running only until symptoms began, running through pain, and stretching into the painful range, and symptoms were only progressing. So again, with the graded exposure approach, we would also be stuck.

Our approach

Step one is diagnosis. The subjective history and examination findings suggested a stretch injury to the superficial peroneal nerve. Given the report of numbness and tingling in the subjective, our primary hypothesis was already something nerve-related. Because she reported a potential inversion ankle sprain, it was still important to conduct a complete exam to rule out other possible diagnoses. Perhaps surprisingly given the mechanism of injury (a hard fall), a thorough exam of the foot and ankle was essentially negative. So we dug a little deeper, conducting specific nerve tension tests for the lower extremity, along with a thorough palpation. When nerves are injured, they can become very sensitive to stretch or tension, as well as compression. A stretch test of the superficial peroneal nerve, and palpation along the approximate path of the nerve’s distal aspect, recreated the patient’s symptoms. This led us to be fairly confident in diagnosing a superficial peroneal nerve stretch injury.

We can't overstate enough here how important it is for clinicians to be nuanced and thorough in their initial evaluations, regardless of which approach they take. Taking a subjective history is not enough. This athlete reported a potential inversion ankle sprain, but had almost none of the typical clinical findings associated with an anterior talofibular ligament sprain. If we treated her with a "standard" ankle sprain protocol, we likely would have missed her injury altogether.

Diagnosis-specific treatment

The next step is treatment. Because the diagnostic process is not perfect, the initial treatment is critical. We want to confirm our diagnosis with treatment. We spent the next 30 minutes performing manual lymphatic drainage along the course of the peroneal nerve, followed by a rhythmic mobilization of the nerve. This dramatically reduced symptoms, helping to confirm our diagnosis. If treatment made no effect on symptoms, then we would have needed to ask two important questions:

- "Was the treatment appropriate for the diagnosis, performed correctly, and performed for an adequate duration?"

- If the answer to question 1 is "Yes," then the clinician must ask, "Is the diagnosis correct?"

We're not looking necessarily for complete resolution of symptoms with the trial treatment (see Tissue Healing Times, and What It Means For You), but we are looking for a significant reduction in order to confirm our diagnosis. If we don't see a positive effect on symptoms, then we can't yet be confident in our diagnosis, and should consider other possibilities. With this patient, our treatment made a big difference.

Considering her diagnosis, it now made sense why her attempt at self management (stretching) only exacerbated symptoms: this movement tensioned the peroneal nerve, further aggravating the injured tissue.

Our instructions for self-management included:

- Self massage along the course of the nerve.

- Avoid stretching into plantarflexion and inversion for now. The nerve will eventually be able to tolerate this motion, but currently it is irritated and sensitive.

- Perform a peroneal nerve mobilization for several minutes, several times per day.

- If symptoms come on during running, perform the mobilization, along with calf raises.

- Our thought with the calf raises: The peroneal nerve runs through the anterior tibialis. Overactivity of this muscle could be contributing symptoms. Calf raises are worth a shot to increase posterior muscle activation.

- Use a strip of tape on the lateral ankle to improve proprioception (link), and perform single leg balance exercises, as long as they do not provoke symptoms.

The results

The patient was nearly symptom-free after treatment, and she was able to run a 100km (that’s 62 miles!) race less than a week later. Here’s what she said about the process:

"I slipped on some ice out on a run, fell, and injured my right leg, and wasn’t able to train due to shin and ankle pain. Brian got me in on very late notice, and didn’t blink an eye when I told him that despite my injury I was hoping to run a 100k in less than a week. That would NEVER happen at my old PT office.

In under an hour Brian diagnosed my nerve injury, gave me a treatment that helped alleviate some of the pain I was experiencing immediately, observed that my own attempts to cure myself were further inflaming the injury, and gave me a few exercises that helped get me back to running that day. He even followed up with me after my return to running the next day, gave me tape for my race, and talked me through the physiology of my injury. I raced the Sean O’Brien 100k less than a week later and placed 3rd."

Graded exposure and treatment of impairments do have a role

What’s perhaps interesting about our approach is that we returned to both the impairment-based and graded exposure approaches after reaching a diagnosis and performing diagnosis-specific treatment. It is of course important for this athlete to restore single leg balance and motor control around the ankle joint. We will definitely want her to move her ankle into plantarflexion and inversion again, in time. But we need to do this while respecting her diagnosis and the injured tissue.

Final thoughts: diagnosis matters

We believe that this concept has far-reaching implications into the conservative musculoskeletal management of pain and injuries. We find that many people who have struggled with a particular injury have either been misdiagnosed, or have been managed in a way that is not specific to their diagnosis.

A few examples:

“Plantar fasciitis” - Pain around the plantar heel or arch of the foot is often labelled plantar fasciitis. We often uncover peripheral nerve injuries, or tendon/muscle injuries. In these cases, classic plantar fasciitis treatment, such as towel scrunches or calf raises emphasizing the plantar fascia, can be aggravating rather than helpful.

“Patellofemoral syndrome” - Anterior knee pain is often given the general term patellofemoral syndrome, and treated with a variety of hip and knee strengthening exercises, and perhaps some taping. We often uncover subtle meniscus injuries, or patellar/quadricep tendinopathies. While we encourage nearly everyone to improve their strength, we’ve helped patients get better, faster results by starting with diagnosis-specific treatments.

“IT band syndrome” - Again, there are many causes for pain on the lateral aspect of the knee. Injuries to the lateral meniscus, proximal calf, biceps femoris tendon, and LCL all caused pain in that area, and should be managed differently than irritation to the distal IT band.

“Shin splints” - There are many different causes of shin pain. Potential pain generators include muscle, nerve, bone, vascular issues, and referral from the spine. You better believe that each of these is managed differently.

If you're struggling with pain or an injury, we'd love to help diagnose it correctly and get you on the road to recovery. We offer free 15-minute phone consultations to help talk through your injury and how we can potentially manage it together. Click below to schedule a free call.